Researchers are now asking wildland firefighters to wear silicone wristbands that absorb organic chemicals in the environment. They hope to use these low-cost, noninvasive, passive detectors as an additional tool to track the array of potentially harmful compounds firefighters may be exposed to. Although the wristbands have some limitations, they allow researchers to detect many chemicals that may otherwise be difficult to measure in the body—“in addition to ones that you can’t measure,” Burgess says.

Investigate Midwest News Story

Univision Noticias placed silicone wristbands on 10 farmworkers, which showed that all of them were exposed to multiple pesticides as they went about their daily lives. That’s in line with findings from multiple scientists.

Their stories show the consequences of pesticide exposure and how regulation falls short of protecting them in one of the countries with the highest rates of pesticide application in the world.

Personal exposure to pesticides has not been well characterized, especially among adolescents. We used silicone wristbands to assess pesticide exposure in 14 to 16 year old Latina girls (N = 97) living in the agricultural Salinas Valley, California, USA.

The results suggest that both nearby agricultural pesticide use and individual behaviors are associated with pesticide exposures.

When Hurricane Harvey swept through the Houston area last August, it caused devastating floods. Many residents worried those floodwaters had swept toxic chemicals into their neighborhoods. It was a concern shared by scientists from Oregon State University.

First made popular by Lance Armstrong’s yellow Livestrong bands, silicone wristbands have gained new popularity among public health specialists wanting to study individuals’ unique exposures. The wristbands are a low-cost, shelf-stable, easy-to-transport, and easy-to-store passive sampling device.

In Harvey’s wake, multiple research teams sprang into action. In the biggest Harvey wristband study, a team at Baylor College of Medicine (BCM) deployed wristbands in three communities around Houston that experienced different types of flooding.

Walker and her team—as well as the other researchers working on post-Harvey exposure studies—believe that reporting findings back to affected communities is especially important when doing science amid a natural disaster. The data from all the Harvey wristband studies will be shared with participants so they can understand their chemical exposures.

Currently there is a lack of inexpensive, easy-to-use technology to evaluate human exposure to environmental chemicals, including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs). This is the first study in which silicone wristbands were deployed alongside two traditional personal PAH exposure assessment methods: active air monitoring with samplers (i.e., polyurethane foam (PUF) and filter) housed in backpacks, and biological sampling with urine. We demonstrate that wristbands worn for 48 h in a non-occupational setting recover semivolatile PAHs, and we compare levels of PAHs in wristbands to PAHs in PUFs-filters and to hydroxy-PAH (OH-PAH) biomarkers in urine. We deployed all samplers simultaneously for 48 h on 22 pregnant women in an established urban birth cohort. Each woman provided one spot urine sample at the end of the 48-h period. Wristbands recovered PAHs with similar detection frequencies to PUFs-filters. Of the 62 PAHs tested for in the 22 wristbands, 51 PAHs were detected in at least one wristband. In this cohort of pregnant women, we found more significant correlations between OH-PAHs and PAHs in wristbands than between OH-PAHs and PAHs in PUFs-filters. Only two comparisons between PAHs in PUFs-filters and OH-PAHs correlated significantly (rs = 0.53 and p = 0.01; rs = 0.44 and p = 0.04), whereas six comparisons between PAHs in wristbands and OH-PAHs correlated significantly (rs = 0.44 to 0.76 and p = 0.04 to <0.0001). These results support the utility of wristbands as a biologically relevant exposure assessment tool which can be easily integrated into environmental health studies.

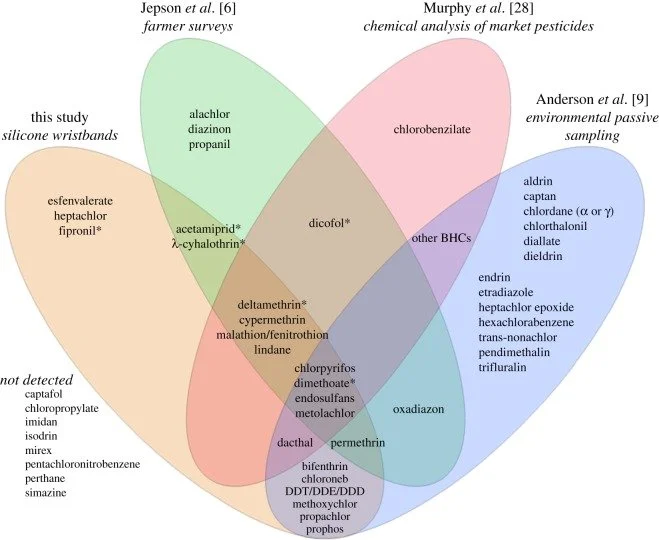

Silicone Wristband Passive Samplers Yield Highly Individualized Pesticide Residue Exposure Profiles.

Monitoring human exposure to pesticides and pesticide residues (PRs) remains crucial for informing public health policies, despite strict regulation of plant protection product and biocide use. We used 72 low-cost silicone wristbands as noninvasive passive samplers to assess cumulative 5-day exposure of 30 individuals to polar PRs. Ethyl acetate extraction and LC-MS/MS analysis were used for the identification of PRs. Thirty-one PRs were detected of which 15 PRs (48%) were detected only in worn wristbands, not in environmental controls. The PRs included 16 fungicides (52%), 8 insecticides (26%), 2 herbicides (6%), 3 pesticide derivatives (10%), 1 insect repellent (3%), and 1 pesticide synergist (3%). Five detected pesticides were not approved for plant protection use in the EU. Smoking and dietary habits that favor vegetable consumption were associated with higher numbers and higher cumulative concentrations of PRs in wristbands. Wristbands featured unique PR combinations. Our results suggest both environment and diet contributed to PR exposure in our study group. Silicone wristbands could serve as sensitive passive samplers to screen population-wide cumulative dietary and environmental exposure to authorized, unauthorized and banned pesticides.

Exposure monitoring with personal silicone wristband samplers was demonstrated in Peru in four agriculture and urban communities where logistic and practical constraints hinder use of more traditional approaches. Wristbands and associated methods enabled quantitation of 63 pesticides and screening for 1397 chemicals including environmental contaminants and personal care products.

Wristbands are increasingly used for assessing personal chemical exposures. Unlike some exposure assessment tools, guidelines for wristbands, such as preparation, applicable chemicals, and transport and storage logistics, are lacking. We tested the wristband’s capacity to capture and retain 148 chemicals including polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs), pesticides, flame retardants, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), and volatile organic chemicals (VOCs). The chemicals span a wide range of physical–chemical properties, with log octanol–air partitioning coefficients from 2.1 to 13.7. All chemicals were quantitatively and precisely recovered from initial exposures, averaging 102% recovery with relative SD ≤ 21%. In simulated transport conditions at +30 °C, SVOCs were stable up to 1 month (average: 104%) and VOC levels were unchanged (average: 99%) for 7 days. During long-term storage at − 20 °C up to 3 (VOCs) or 6 months (SVOCs), all chemical levels were stable from chemical degradation or diffusional losses, averaging 110%. Applying a paired wristband/active sampler study with human participants, the first estimates of wristband–air partitioning coefficients for PAHs are presented to aid in environmental air concentration estimates. Extrapolation of these stability results to other chemicals within the same physical–chemical parameters is expected to yield similar results. As we better define wristband characteristics, wristbands can be better integrated in exposure science and epidemiological studies.

Our approach combines silicone wristband personal samplers and DNA damage quantification from hair follicles, and was tested as part of a community-based participatory research (CBPR) project involving ten Latino children from farmworker households in North Carolina.

We detected between 2 and 10 pesticides per person with novel sampling devices worn by 35 participants who were actively engaged in farming in Diender, Senegal. Participants were recruited to wear silicone wristbands for each of two separate periods of up to 5 days.

Organophosphate flame retardants (PFRs) are widely used as replacements for polybrominated diphenyl ethers in consumer products. With high detection in indoor environments and increasing toxicological evidence suggesting a potential for adverse health effects, there is a growing need for reliable exposure metrics to examine individual exposures to PFRs. Silicone wristbands have been used as passive air samplers for quantifying exposure in the general population and occupational exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.

A simple way to track your everyday exposure to chemicals

Silicone wristbands mimic how the body absorbs toxic compounds

For one week, 92 preschool-aged children in Oregon sported colorful silicone wristbands provided by researchers from Oregon State University. The children’s parents then returned the bands, which the researchers analyzed to determine whether the youngsters had been exposed to flame retardants. The scientists were surprised to find that the kids were exposed to many polybrominated diphenyl ethers (PBDEs), chemicals that are no longer produced in the U.S., as well as to organophosphate flame retardants, which are widely used as substitutes for PBDEs.

Silicone wristbands can be used as passive sampling tools for measuring personal environmental exposure to organic compounds. Due to the lightweight and simple design, the wristband may be a useful technique for measuring children's exposure.

During a single week back in August in which I bopped in and around New York City, I was exposed to at least 16 hazardous chemicals. These included phthalate chemicals of the type banned in kids toys and pacifiers, flame retardants such as TCPP and TPP, and Galaxolide, a common fragrance found in cleaning and beauty products.

I’m aware of the sobering details because of a wearable.

This Wristband Will Tell You Which Chemicals You're Exposed To Every Day

We live in a pretty toxic world. How toxic? This new wearable will let you know—and you probably won't like the results.

We tend to blame bad genes for breast cancer and Alzheimer's, but few diseases are purely genetic. The "exposome"—all the things we're exposed to throughout our lives—often plays a bigger role than DNA. That includes the obvious, like diet and exercise, but also factors that are harder to track, like the chemicals that surround us.

A new wearable called MyExposome is designed to reveal which chemicals are actually part of your everyday life. Strap on the wristband for a week, and it absorbs chemicals—from pesticides to flame retardants—along with you. At the end of the week, you mail it back to a lab to learn about the invisible part of your world.